Festival Folly?

The (Mis)Representation of Desi Festivals in Western Media

By Priya Kiran

Seeing a South Asian face in an American television show is always a shock followed by excitement in my household. It begins with my sisters and I thinking to ourselves, “Hey! They look desi!”, and is immediately followed by my father animatedly announcing, “This person most definitely is Indian, what’s their name? Look it up right now!”

Now if the show goes so far as to include a desi holiday or festival, then we get more invested and, to be honest, analytical. We break apart what each character says, how they describe the holiday, the rituals, the reasoning, and we discuss and debate to determine if the select festival was appreciated or appropriated? Was it used as an exhibition to emphasize exoticism or as a genuine gesture to be inclusive? And we eventually end up wondering if we should just be thankful for the representation, and hope that it will get better in the future?

To hope for the future, first we have to acknowledge the past. So come with me to a memory that I hold near and dear to my heart – the first time I ever saw an Indian festival celebrated in Western media… “The Cheetah Girls: One World”(2008, dir. Paul Hoen). In this film, the singing and dancing troupe, now a trio (shedding a tear for Raven Symoné) travels to India to star in a Bollywood film to jumpstart their popstar dreams once again. I’ll admit this film was nowhere near as good as its predecessors, but you best believe on August 12th, 2008 I was sitting with my sister in front of the TV in our basement, ready for the premiere. We watched, we laughed, and we definitely judged, but ultimately seeing our culture on screen was veritably magical… at that moment. Reflecting on it now, the way they displayed and used parts of Indian culture, specifically the festivals, makes me sad.

In one scene, the Cheetah Girls and a film crew on a location scout travel to a palace where they are welcomed by a grand parade of dandiya dancers, elephants, and people throwing coloured powder. The background music is the song “Aayo Holi” from the film, “Bawandar” (2000, dir. Jag Mundhra). If my family and I were to break down this scene the way we do now — there is no reasoning why everyone is celebrating. It is just an ostentatious sequence that this is all there is to India — people swathed in saturated colour, dancing with their pet elephants. However, seeing it as a child, I could only assume that “this is how you’re welcomed when you enter a palace in India”. Holi was used purely for the decoration and spectacle, which is really quite sad for a film that had such a large reach on young audiences all over the world. One could say, “Oh, pc culture wasn’t a thing yet, maybe the filmmakers truly didn’t know how to authentically present it?”. Well, even before pc culture had even been coined and wholly recognised, there were Western filmmakers who were able to explore Indian festivals with reverence and appropriately include them into their narratives, not just for the sake of it, but as an instrumental event that shapes the world of their story and thus, the experience of their film.

We now venture even further into film history – to the 1960s and 70s. A time when the world seemed to have rediscovered India. Western women were dawning kurtas, sitars could be heard on the radio, and tantric ideologies were all the rage. One production company rode the wave of this revolution and brought change to their industry as well— Merchant Ivory Productions. This company was founded by American producer, writer, and director, James Ivory and his business but also life partner, Indian film producer, writer and director, Ismail Merchant. They set out “to make English-language films in India aimed at the international market” – and they did just that. You may have come across James Ivory in recent years as the screenwriter and one of the producers of the Academy Award Winning film, “Call Me By Your Name” (2017, dir. Luca Guadagnino)

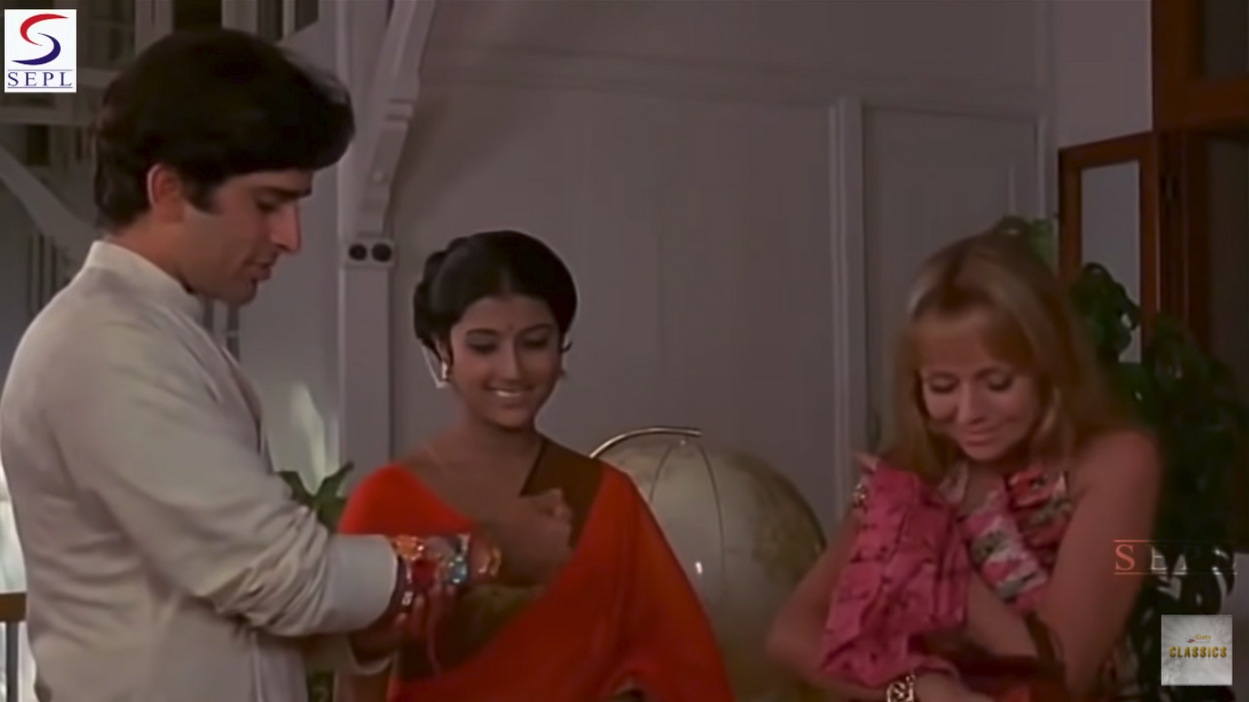

Ivory and Merchant’s films often starred the legendary Shashi Kapoor, usually opposite a beautiful, British heroine. They were shot in India, and the dialogue would switch between English and Hindi. Merchant, himself being of Indian origin, would usually oversee most of the films, adhering to authenticity and respectful portrayal of Indian traditions and festivals. One of my favourite and most dramatic inclusions of an Indian festival was in the film, “Bombay Talkie” – Raksha Bandhan. All these beautiful women are tying rakhis to Shashi Kapoor’s wrist, while his wife proudly stands behind him. Enter “other woman” and femme fatale, Jennifer Kendal, who wants to gift him a watch. Shashi’s wife is jealous of this “other woman” and explains that she cannot gift him a watch, she must tie a rakhi. This insinuates that upon tying this rakhi, for Shashi Kapoor’s character to engage with this “other woman” beyond a familial bond is the utmost form of taboo. Raksha Bandhan is implemented as means of conflict, pushing the narrative by means of adhering to the festival’s values. This is explained through dialogue in the film. So even in this era of history, where “pc culture” did not exist in the slightest, Indian culture was receiving authentic and respectful representation on screen. Where did it go wrong?

Since then, Desi representation has taken a backseat in Western, and majorly, Hollywood productions. Every so often you’d see a South Asian character playing a stereotypical role of “taxi driver”, “fortune teller”, “motel owner”, and the list goes on. Indeed, stereotypes are observed and not created, and these roles that are presented in Hollywood are result of the influx of Indian immigrants seeking work and a better quality of life, but does that mean we have ourselves to blame for American media continuing to perpetuate the stereotype? And by perpetuating the bare minimum of representation, how can we expect festivals to be represented and that too, with authenticity that does not mock our heritage and our rich history? Granted, there has been a slight turn of the tide, we have the iconic Diwali episode from “The Office” (I mean, who else was doing that in 2006?), or the chaotic, but hilariously relatable Mundan ceremony in “The Mindy Project” (note the common factor here — Mindy Kaling) in contrast to the more recent, quite problematic, and cringe-worthy Diwali episode from “And Just Like That”, or for that matter the entire existence of the 2010 American sitcom, “Outsourced” (which my family and I did watch, because again, we were just happy to see desis on screen). Before we demand or emphasize on more representation on screen, we first need authenticity. And for that to happen we need more representation behind the scenes.

On April 27th, 2020, “Never Have I Ever” aired “[Never Have I Ever]…Felt Super Indian”. In that episode, Mindy Kaling and her team of writers portray Ganesh Chaturthi celebrated in an American suburb. They showcase it through the eyes of a first generation Indian-American teenager, and this influences the emotions, the fashion, the awkwardness, the drama and even, the beauty of an Indian festival, even if it does take place in a high school gym.

Just over a year later,on August 13th, 2021, “Spin!” (2021, dir. Manjari Makijany) was released — a Disney channel original movie about Rhea, an Indian-American teenager who discovered her passion in becoming a DJ. In this film, they have a fundraiser for their homecoming called “the Festival of Color”, which was Rhea’s idea. In the film she explains how it’s based off of Holi, and what the festival signifies. This film premiered exactly 14 years (and one day) after “The Cheetah Girls: One World” and is a direct comparison to how filmmakers are treating desi festivals. We have a long way to go, but this is why I have so much hope for where the future of authentic representation is headed. The opportunity to showcase our candid perspectives and narratives bring about a more magical experience for that next little Indian-American girl sitting in her basement in front of her TV seeing not just her culture and heritage, but “herself” on the screen. This is a future I definitely want to be a part of!